Codifying the Build and Release Process with a Pipeline Shared Library

| This is a guest post by Alvin Huang, DevOps Engineer at FireEye. |

As a security company, FireEye relentlessly protects our customers from cyber attacks. To act quickly on intelligence and expertise learned, the feedback loop from the front lines to features and capabilities in software must be small. Jenkins helps us achieve this by allowing us to build, test, and deploy to our hardware and software platforms faster, so we can stop the bad guys before they reach our customers.

More capabilities and functionalities in our product offerings means more applications and systems, which means more software builds and jobs in Jenkins. Within the FaaS (FireEye as a Service) organization, the tens of Jenkins jobs that were manageable manually in the web GUI quickly grew to hundreds of jobs that required more automation. Along the way, we outgrew our old legacy datacenter and were tasked with migrating 150+ Freestyle jobs on an old 1.x Jenkins instance to a newer 2.x instance in the new datacenter in 60 days.

Copying Freestyle job XML configuration files to the new server would leave technical debt. Using Freestyle job templates would be better but for complicated jobs that require multiple templates, this would still create large dependency chains that would be hard to trace in the log output. Finally, developers were not excited about having to replicate global changes, such as add an email recipient when a new member joins the team, across tens of jobs manually or using the Configuration Slicer. We needed a way to migrate the jobs in a timely fashion while getting rid of as much technical debt as possible.

Jenkins Pipeline to the rescue! In 2.0, Jenkins added the capability to create pipelines as first- class entities. At FireEye, we leveraged many of the features available in pipeline to aid in the migration process including the ability to:

-

create Pipeline as Code in a

Jenkinsfilestored in SCM -

create Jenkins projects automatically when new branches or repos get added with a

Jenkinsfile -

continue jobs after the Jenkins controller or build agent crashes

-

and most importantly, build a Pipeline Shared Library that keeps projects DRY and allows new applications to be on boarded into Jenkins within seconds

However, Jenkins Pipeline came with a DSL that our users would have to learn to translate their Freestyle jobs to pipeline jobs. This would be a significant undertaking across multiple teams just to create Jenkins jobs. Instead, the DevOps team identified similarities across all the Freestyle jobs that we were migrating, learned the Jenkins DSL to become SMEs for the organization, and built a shared library of functions and wrappers that saved each Dev/QA engineer hours of time.

Below is an example function we created to promote builds in Artifactory:

def call(source_repo, target_repo, build_name, build_number) {

stage('Promote to Production repo') {

milestone label: 'promote to production'

input 'Promote this build to Production?'

node {

Artifactory.server(getArtifactoryServerID()).promote([

'buildName' : build_name,

'buildNumber' : build_number,

'targetRepo' : target_repo,

'sourceRepo' : source_repo,

'copy' : true,

])

}

}

def call(source_repo, target_repo) {

buildInfo = getBuildInfo()

call(source_repo, target_repo, buildInfo.name, buildInfo.number)

}Rather than learning the Jenkins DSL and looking up how the Artifactory Plugin worked in Pipeline, users could easily call this function and pass it parameters to do the promotion work for them. In the Shared Library, we can also create build wrappers of opinionated workflows, that encompasses multiple functions, based on a set of parameters defined in the Jenkinsfile. In addition to migrating the jobs, we also had to migrate the build agents. No one knew the exact list of packages, versions, and build tools installed on each build server, so rebuilding them would be extremely difficult. Rather than copying the VMs or trying to figure out what packages were on the build agents, we opted to use Docker to build containers with all dependencies needed for an application.

I hope you will join me at my Jenkins World session:

Codifying the Build and Release Process with a Jenkins

Pipeline Shared Library, as I deep dive into the inner workings of our Shared

Pipeline Library and explore how we integrated Docker into our CI/CD pipeline.

Come see how we can turn a Jenkinsfile with just a set of parameters like this:

standardBuild {

machine = 'docker'

dev_branch = 'develop'

release_branch = 'master'

artifact_apttern = '*.rpm'

html_pattern = [keepAll: true, reportDir: '.', reportFiles: 'output.html', reportName: 'OutputReport']

dev_repo = 'pipeline-examples-dev'

prod_repo = 'pipeline-examples-prod'

pr_script = 'make prs'

dev_script = 'make dev'

release_script = 'make release'

}and a Dockerfile like this:

FROM faas/el7-python:base

RUN yum install -y python-virtualenv \

rpm-build && \

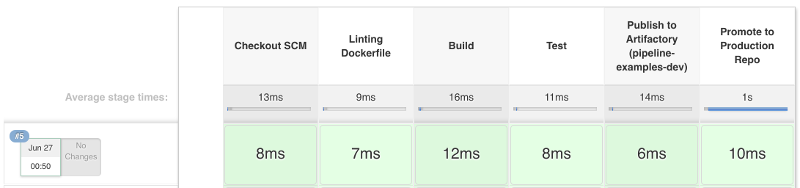

yum clean allInto a full Jenkins Pipeline like this:

As we look ahead at FireEye, I will explore how the Shared Library sets us up for easier future migrations of other tools such as Puppet, JIRA, and Artifactory, and easier integration with new tools like Openshift. I will also cover our strategies for deployments and plans to move to Declarative Pipeline.

|

Alvin will be

presenting

more on this topic at

Jenkins World in August,

register with the code |